- Home

- Mukunda Rao

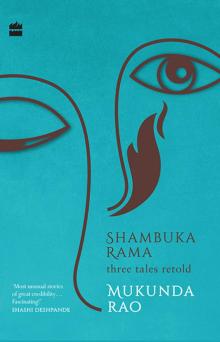

Shambuka Rama

Shambuka Rama Read online

SHAMBUKA RAMA

Three Tales Retold

MUKUNDA RAO

CONTENTS

ANOTHER BHEEMA

SANJAYA SPEAKS

SHAMBUKA RAMA

About the Book

About the Author

Copyright

ANOTHER BHEEMA

EXHAUSTED THEY LAY FLAT on the ground, breathing heavily, filling their lungs with the fresh mountain air. Kunti breathed a sigh of relief and thanked God for blessing her with a son like Bheema. Arjuna smiled tiredly, thinking how weak he was in body compared to Bheema, who stood on a nearby rock, like a colossus under the full moon, gazing into space. The sky had turned red, lit up by the flames erupting from the house they had just escaped from. He let out a cry of rage and swore to the heavens, while the Ganga flowed by serenely, a disinterested witness to the pains and joys of human life over the ages.

‘Bheema,’ said Yudhishthira, ‘without you, we would have been dead by now.’

Bheema turned and replied angrily. ‘Brother Yudhishthira, you forget the miner. If he had not dug the tunnel in time for us, we would have been roasted alive by now.’

‘How true!’ exclaimed Kunti. He might be a lowborn miner but he was truly their saviour. ‘Yudhishthira,’ Kunti continued, ‘you must never forget this man. When you become the king you must find him, thank him and honour him properly.’

‘Yes, Mother.’ Yudhishthira agreed, and then he was struck by pangs of guilt, thinking of Purochana and the tribal family they had left behind to die in the fire at the House of Lac. The Pandavas had got them drunk and let them perish in the fire, while they made their escape. The charred bodies of the tribal woman and her five sons would be mistaken for the Pandavas. This is how they decided to save themselves when they came to know of Duryodhana’s plot to kill them.

This plan, Yudhishthira suddenly realized with horror, was as wicked as Duryodhana’s evil plot to exterminate them. A fearful shudder shook his body as the flames leapt to the skies in a maddening frenzy. Can adharma be annulled by another act of adharma? Is it better to suffer adharma or to fight it? His head grew hot with doubt and tears filled his eyes, like an ancient grief unable to wash itself clean. He would carry this grief, this act of adharma like a wound concealed under his clothing, only to add many more to it as time went by. And these wounds would destroy his peace, his centre.

Yudhishthira heard a sound and turned to see a figure emerge from behind a tree. A man approached him with long strides and said, ‘Ah, you must be Yudhishthira, the man of dharma; my pranam to you. I’m the boatman sent by master Vidura to ferry you all across the Ganga.’ Then, going up to Bheema, he exclaimed, ‘You must be Bheema, the great fighter!’ Finally, he fell at Kunti’s feet. ‘I know you are Mother Kunti. Bless me, Mother,’ he prayed, ‘bless me with five sons such as yours.’

‘What is your name?’ Kunti asked.

‘I’m a boatman. I’m a child of Ganga.’

‘But you do have a name, don’t you?’ Arjuna said.

‘Ah, you must be the handsome Arjuna, the greatest archer in the world. Yes, sir, I’m Gangaputra. Come now, let me take you all to safety. Mother Ganga is sleeping; come, let’s not disturb her.’

The boat was large enough for the Pandavas. Kunti sat in the middle with her sons around her. The boatman sat at one end, rowing the boat gently. He smiled often and one could not say what he was thinking. The river murmured, it seemed in approval, and the full moon smiled gaily. The boatman said, ‘It is indeed my great fortune to guide the great Pandavas to safety. I’m blessed.’

‘My dear brother,’ Yudhishthira said, ‘we are indebted to you. We will never forget your timely help.’

Caressed by the river breeze, while the others tried to rest and find their equilibrium after their recent experience, Bheema continued to seethe with anger. The boatman chuckled and began to sing:

Take us, O boat, take us

to the distant shore,

take us home.

Fly, O boat, fly

like the garuda without ado,

fly us to our heavenly home…

Bheema was annoyed by the boatman’s cheerful mood. The scene around them was so serene but he could not reach that serenity. He could have simply stretched his hand and caressed the purling river, leant back and watched the moon playing hide-and-seek with the clouds, allowed the breeze to wash over him, and given himself up to the song. But he sat stiff, staring at nothing in particular. Why? Why was he always on edge, always agitated over something or the other? Couldn’t he ever relax?

Over the last few years, something terrible had been happening to him, something that was turning him into a wrathful, revengeful demon. The fifteen years of life in the Himalayan valley of Satashringa had been one of pure joy and harmony. As a child of nature, one with the cosmos, he had known no conflict, no hatred, no desire for power. But their coming to the city of Hastinapura had turned everything topsy-turvy, and their minds had become unhinged with the knowledge that they were princes who had a claim to the throne of Hastinapura.

There was no going back now; still, deep in his heart, Bheema remained a child of the forest, and he would never be entirely at peace with himself and the world as a prince. Whenever he thought of the Kauravas, and saw Duryodhana’s face in his mind, he felt he would go mad with rage. He was only in his twenties. How would he be in another twenty years? What kind of a future awaited him? Karma was deceptive. He must grow to be more cunning to cheat his karma if he wanted to reach the shore of happiness. He looked back and saw the dying flames on the other shore. Once again, his body convulsed with anger.

The brothers awoke just as the boat reached the shore. The boatman said, ‘Good, you rested for a while and recovered your strength. But your brother Bheema kept awake like a god who needs neither rest nor sleep to keep him alive.’

The brothers did not respond. They knew.

Gangaputra took them home. His wife, dark and beautiful, was all smiles and warmly affectionate, and offered the guests a meal of rice gruel and river fish cooked in coconut milk. The boatman’s six-year-old son, stout and handsome, talked continuously and was full of sharp questions. The Pandavas were hugely entertained. Even Bheema who, just a short while ago, had been growling like an incarcerated lion, roared with laughter at the little fellow’s antics and amusing queries. At that moment, it seemed to Bheema that he was reliving his childhood days. The boy also enjoyed the jocund company of the extraordinary guests, and was fascinated by Bheema’s great physique. When he wanted to know how he could possibly develop such a prodigious body, Arjuna suggested playfully, ‘Eat like a rakshasa.’ Thus, the Pandavas forgot their fears and distress and spent the night in a jovial mood.

They left in a hurry early the next morning. Duryodhana’s spies were everywhere. They did not want their evil cousin to know that the bodies in the House of Lac were not that of the Pandavas. They had to go incognito for sometime, plan things carefully and gather support before making any attempt to regain their right to the throne. They travelled the entire morning and, at noon, stopped by a lake to refresh themselves with a bath and a meal of fruits. Then they decided to rest awhile.

As they lay down under the shade of a great tree, Bheema, who had kept mum throughout the journey, suddenly exploded in anger: ‘This is shameful, running away like cowards. No, I can’t take this any more; I’m going back to Hastinapura. I can’t rest until I squeeze the life out of Duryodhana and smash the head of his blind father. I won’t take this betrayal lying down.’

‘Be patient, Bheema,’ Yudhishthira cautioned gently. ‘Haste kills a man. Returning to Hastinapura will be like walking into a death trap.’

‘I prefer to die fighting as a Kshatriya than running under cover like a

frightened animal.’

Kunti said, ‘Bheema, you know, if not for Vidura, we would all be dead by now. We must believe in his wisdom. Both Vidura and your grandfather Vyasa know what is best for us. We must wait for their message.’

Bheema turned to his other brothers for support. But they all looked away, for they dare not contradict their mother or their eldest brother. Arjuna appeared not entirely in agreement with the escape plan, but even he would not speak his mind. Bheema leaned against the trunk of the tree and groaned with disgust. This was absurd. This could not be called living. He felt he was not alive at all, alive to the throbbing life in and around him. He thought he had to do something soon or he would burst with the anger he was carrying within.

When they entered the awesome forest, the sun was behind them and the shadows had lengthened. It was at once a haven of peace and tranquillity, and a forest of death. It was the home of the Yamas, people who had turned their backs on civilization, to the tyranny of the warring Kshatriya kings and the Brahman culture. The forest was also inhabited by a tribe of rakshasas, who were powerful and had huge physiques, and lived on animal and human flesh. And then there were the forest animals, wild and dangerous; they came alive at night and hunted their prey at lightning speed.

The Pandavas had to cross this forest to reach Ekachakra where, on the advice of Vyasa, they had planned to live in hiding. But would they survive the journey through a forest infested with such dangers? Kunti was worried. There was something enchanting and tempting, but strangely disturbing, about the forest, and this was more unsettling than the fear of animals and demons.

The trees here were huge and tall; the trunks were so thick that one could carve out houses in them. Wild flowers of various hues looked like benevolent, handsome monsters. And the ground was a thick carpet of green. The silence was overwhelming; it seemed to seep into their bones and change their whole attitude to life. Existence here seemed to be of a different order. It was truly a world of maya. It grew and stretched beyond one’s vision, like Hanuman’s tail.

‘Let’s rest for a while,’ said Kunti, and sat down on the grass, oddly softer and more comforting than the silk cushions of the palace. She was not so much tired in body as worried mentally. ‘What do you think, Yudhishthira?’ she asked.

‘Mother, this forest reminds me of Satashringa,’ said Yudhishthira. ‘I feel light and soft like a breeze, and that somehow frightens me.’

‘Should you always feel heavy, brother?’ Bheema teased him.

‘There is something wild and dangerous about this forest,’ said Arjuna.

Nakula and Sahadeva nodded in agreement. ‘Yes,’ said Kunti. ‘In Satashringa, even when you were all gone for the whole day, I was never troubled with any doubt or fear about your safety. But here’ She shook her head and added, ‘somehow, I’m scared.’ Then she looked at each of her sons’ faces and said with some emphasis, ‘You are no more the children of the forest. It was fate that kept you all away from your rightful place as the princes of Hastinapura. You must stay together now and never forget that you are Kshatriyas, that you are the Pandavas.’

‘I don’t know,’ muttered Bheema, and stood up, yawning. Mother never tired of reminding them that their vocation was to be the princes of Hastinapura. If they were born princes, why then did they have to live in the forest of Satashringa for fifteen years? If Father had not died, would they have come to Hastinapura? There were too many gaps in the story, and their mother was not forthcoming with explanations.

‘Let me climb a tree and see how far this dreadful forest stretches,’ said Bheema. As he looked up a tree that seemed to touch the sky, he spotted a strange bird on one of its branches, and cried out in excitement. The bird was as big as a human being, sporting a colourful crown and beard, and its feathers were long and thick, burning bright like stars. The next moment the bird leapt, spreading its huge, dazzling wings, and disappeared through the thick foliage.

‘Sons,’ Kunti called suddenly, and drew their attention to a figure approaching in the distance. It seemed as if the strange bird had now taken the form of a human being. He had a hooked nose, hair that fell over his shoulders, and a brown beard. Clad in a gown that covered his body, he looked an integral part of the forest. Yudhishthira greeted him with respect and said, ‘We are the Pandavas and this is our mother. We are on our way to Ekachakra.’

It was difficult to determine the age of the man. He could have been a hundred years old, or just fifty. His lips, covered by a thick moustache, stretched into a smile as he said, ‘I know you are in trouble.’ His voice was soft and his eyes full of pity.

‘Who are you?’ Arjuna asked.

The man smiled. Arjuna took an instant dislike for him.

‘Could you please tell us a safe place to stay?’ Kunti asked.

‘Your sons are warriors. There cannot be any danger to you. Perhaps you are the danger here.’

‘You seem to know us.’ Bheema frowned, studying the stranger.

The man smiled again. ‘Yes, I know that you can break the neck of a monster in no time. And your brother there can hit his target even in the dark.’ Then he turned to Yudhishthira and spoke, ‘You look different, quite mature and ready to discover and live in your natural state. Perhaps you can join us, that is, if you want to. The choice is yours.’

‘You appear to be a man of wisdom,’ Yudhishthira said.

‘There is no ignorance here.’

‘You are not being helpful,’ Arjuna retorted.

The man shrugged. Pointing to his right, he said, ‘There is a lake nearby, and trees more comfortable than your palace. The lake water will quench your thirst and hunger.’ Then, as if he did not want to be involved in their affairs any longer, he turned and melted into the dappled shadows.

‘He is no ordinary human being!’ Nakula said.

‘Perhaps a demon in the guise of an old man. We must be careful,’ warned Arjuna.

Kunti thought otherwise. The man was no spirit of the forest; nor was he a demon. He must be one of those Yamas they had heard about. Yudhishthira agreed. Strangely, what the man had said deeply affected him. How he wished to join the tribe of seekers. Left to himself, perhaps he would have, but he was burdened with the responsibility that fell on him as the eldest among the five brothers. He could not forsake his dharma, no, not even for his enlightenment. Their return to Hastinapura had changed everything.

In Satashringa, when his brothers spent the whole day playing and hunting in the forest, he had sought the company of the hermits who lived on the southern slopes of the great Himalayas. The gurus and scholars in Hastinapura were quite knowledgeable, but they lacked the character as well as the depth and vision of the Himalayan mystics. The only exception seemed to be Vidura, with whom he spent long hours discussing spiritual matters, while his brothers willingly and enthusiastically trained in fighting and wrestling.

Despite having their reservations about the stranger, the Pandavas started in the direction the man had indicated, for they had no other option. Soon, they came upon a lake, radiant like a large diamond. Like benevolent spirits, giant trees stood around the lake. The water, clear like the sky, tasted like nectar, and they felt imbued with great energy and joy. It seemed they had entered a mythical space, for they did not know if what was happening to them was real or an illusion.

At dusk, however, the place turned eerie and the lake became a swirling current that seemed hungry to suck them all into its belly. They rested the night on the generous branches of the trees, covering themselves with large, thick leaves. Arjuna insisted that he would keep guard, and Bheema was glad to be relieved of the burden.

The next day, determined to get out of the forest before sunset, they started early and travelled the whole day, but the forest seemed endless. Even Bheema, who never knew fatigue, grew weary; still, he carried Kunti on his back. They broke journey when the sun fell behind the trees, and Kunti cried that she was dying of thirst. She was past all caring. It did not matter whether th

ey would be devoured by animals or demons, or captured by the Kauravas. They needed to rest and quench their thirst.

While they rested in a grove, Bheema went in search of water, following the noise of water birds. Soon, he was at a beautiful lake dotted by innumerable eye-catching lotuses. Tired and thirsty, he drank deeply of the clear water. The water was so cool and thrilling that he was tempted to take a dip and stretch his limbs, cramped by carrying his mother and brothers. He fought the temptation, plucked two huge lotus leaves, made large cups of them and carried water back to the grove.

One by one, they drank the water and went back to sleep again. Bheema had never seen them so tired before. He wondered if there was something in the water that put them to sleep so quickly, though nothing happened to him, and he had drunk the same water. The reality, however, was that their journey had been an arduous one, and the family rested safe in the knowledge that Bheema would keep guard and protect them against danger.

Bheema sat by them and watched. His brothers looked so vulnerable and pathetic in their sleep. Look at Yudhishthira! So young in age, yet more mature than many twice his age, and fit to be the king of the world. He slept on the ground like an exhausted shepherd, supporting his head on his folded arm. By his side lay Arjuna, the finest archer, now an easy target even for a child. And the twins, dark and handsome, who together could face an army of soldiers, but right now, needed his protection. Bheema’s heart melted at the sight of his mother who lay on the grass covered by leaves, like an ordinary village woman. Sister of Vasudeva, wife of the great Pandu, and mother of five brave and powerful sons!

He felt a familiar rage course through his veins, hot white rage towards Dhritharashtra and his son Duryodhana, and even against Bheeshma and the other Kauravas who, he believed, were in some way responsible for their present predicament. ‘Be patient,’ both Yudhishthira and his mother had advised him. But for how long? The more he thought of Duryodhana, the more restless he grew, and the tumult in him rose like a tremendous wave ready to bring down everything before it. If they had never left Satashringa, they would not have had to face these troubles and anxieties. This was fate. Was it his fate to have been born a Kshatriya? Suppose he had been born into a Shudra family and had become a boatman? Ah, the boatman, his wife and son seemed such a content and complete family.

Shambuka Rama

Shambuka Rama