- Home

- Mukunda Rao

Shambuka Rama Page 2

Shambuka Rama Read online

Page 2

It seemed to him that in order to be perfect and happy, one needed to be ordinary and simple. It seemed a curse to be a Kshatriya, burdened by a dharma that could never be fulfilled, dharma that was most often fuelled by hatred and revenge. It seemed like a cruel joke.

He wondered about Yudhishthira. No wonder his brother always looked worried and tense about the rightness of things. What a burden it was to be the eldest, to be held more responsible than the others for everything that happened to the family. Oh, he was blessed to be born second, and how he wished to live a life of irresponsibility and untrammelled joy. All he wanted to do was to go and swim in the lake and forget himself. If only he could somehow change his karma and live the life of the boatman.

As the family slept and Bheema’s mind wandered, they had no idea that they were resting in the dangerous Hidimbavana. Hitherto, no human being who had entered this part of the forest had gone back alive. Hidimba, the rakshasa, had developed a taste for human flesh, and every day he waited for some foolish human to drift in there and satiate his hunger. At that time, like the Pandavas, he was asleep on a tree, snoring wildly.

Now, as a strong breeze swept over him, he woke to the scent of human flesh. He sat up and breathed deeply, letting the smell of the Pandavas course down his guts. ‘Smells of human blood!’ he shouted in great exultation, and rudely woke up his sister, Hidimbi, who lay on a nearby branch.

Sitting up in anger, she said, ‘I was having such a wonderful dream and you spoilt it all.’

‘What dream? I never have dreams,’ he guffawed.

‘That’s why you have become a rakshasa,’ remarked Hidimbi. ‘You know, brother,’ she continued, almost blushing, ‘in the dream, I had changed. I mean…’

‘You mean into a sentimental country girl!’ And he broke into such laughter that the branches shook and the leaves shivered as if in fear. ‘The charming human beings have come out of your dream and are staying somewhere close. Don’t you smell them? Ah, my mouth is already watering at the thought of their delicious flesh! Come on now; go break their necks and get their bodies here. We’ll have a feast.’

‘You know I don’t like human flesh,’ Hidimbi snapped. ‘You like human flesh, you go and get them. Moreover, I’m not hungry.’

‘If you don’t go right away,’ her brother yelled at her, ‘I’ll make a meal of you.’

‘I should have listened to our mother,’ she cried. ‘She had warned me against living with you.’ But Hidimbi was scared of her brother, and there was no way she could have lived alone after the death of their mother, or even joined her mother’s tribe, who lived on the other side of the forest. Her mother’s warning came true the day Hidimba tasted human blood and took to eating human flesh. Till then, they had lived off wild game and there was no dearth of animals in the jungle. But now, hooked on human flesh like a man-eating tiger, he prowled the jungle, preying on unwary tribals.

‘This is the last time I’ll do it for you,’ she said, getting up reluctantly, fearfully. ‘And then I’m gone.’ She flew down the tree and hurried in the direction of the Pandavas.

As she reached the grove where the Pandavas were resting, she hid behind a tree so she could take stock of her prey. She saw a hulking figure of a man sitting on a fallen tree trunk, keeping vigil over a woman and four men sleeping on the ground close to him. Her gaze rested on the giant. She could not believe her eyes, for she had never seen a man who looked like that: broad shoulders, great chest, slim waist, narrow hips and muscular arms – an exquisitely proportioned body. The man looked more alluring than the cool waters of the river and the caress of the breeze in the trees. The thought of killing him and the helpless sleepers melted away and, at that very instant, something in her snapped open.

She felt it in her heart, a feeling like the sea swelling on a full moon night. She knew instantly that he was her man, a man fit to be her lover and lord. Every cell of her body yearned for union, and as these cells cracked in a blinding explosion, releasing great mutating energy, she was transformed into a tall, perfectly formed woman of great beauty. Like a river drawn to the sea, slowly, gracefully she stepped towards Bheema.

Bheema turned at the sound of footsteps, and his eyes grew wide with amazement. In all his life he had not seen a more beautiful woman, not even among the carefully bred women of the royal families. It seemed the figure in front of him, draped in chaste white, like the moon rising from the sea, was Parvati herself come down to please him. Her dark, curly tresses fell gracefully over her naked shoulders, and her eyes, round and large, gleamed like the arrows of kama. He had known his body turn hot with rage, but never had he felt before such warmth in his groin. His body felt as though it were on fire. He remained speechless for a long time. Finally, coming back to his senses, he asked, ‘Who are you? You are so enchantingly beautiful! How is that you are in such a dangerous forest?’

‘You are so handsome, like a great wolf!’ Hidimbi said, blushing like the setting sun. ‘Who are you? And who is this charming woman, and these handsome young men? This is no place for you to rest. Don’t you know that a rakshasa called Hidimba lives here?’

‘Is that so?’ Bheema grinned. ‘We are the Pandavas. No harm can come to us. But tell me, who are you?’

Hidimbi told him the truth. She did not know any other way to talk to him. ‘How can I obey my brother’s command when I have lost my heart to you?’ she asked, her eyes glowing with love and desire. ‘Accept me,’ she said without shame. ‘Take me and be my husband. I’ll make you happy.’ Bheema winced. He could not believe his ears, nor his eyes. The women of Hastinapura would have died with shame, or suffered their passion for a hundred years rather than speak to a man so frankly and plainly about their desire.

But Bheema’s body yearned to be with her, to take her then and there and make her his wife; nothing else seemed to matter. Still, his rational mind and conscience warned him against the impulse. He could not behave like a barbarian. He was a prince. He started laughing, more out of his inner conflict than at her naked love and impulsive surrender to him. Pointing at his mother and brothers who were still in deep slumber, he said, ‘They depend on my strength to protect them and get back to Hastinapura. No, I cannot marry you and abandon them, and abandon my dharma.’ He paused, wondering why he was saying all this to a strange woman.

‘Believe me, I have the power to protect you all against my brother. Let’s go far away from here where my brother can’t reach us. Come with me.’

Bheema laughed. ‘I’m Bheema. I can crush the life out of your brother in no time. Don’t worry. And do not make me go against my dharma. Please leave.’

Helpless tears flooded Hidimbi’s eyes, surprising her. She said, ‘I do not doubt your strength. But all I know is that in my heart I have already accepted you as my lord, and I do not want to lose you.’ She had never felt such passion before, and had never shed tears except when she had been physically hurt.

Just then they heard a sound, like something crashing through the forest. It was Hidimba who, after having waited for his sister, was rushing down to see what had happened. Hidimbi implored Bheema, ‘It’s still not too late. Wake your mother and brothers up and let me take you all to safety.’

‘You do not know my strength.’ Bheema said grimly. ‘Let your brother come. I’ll rid this forest of a monster like him.’

‘All right, I’ll not stop you,’ Hidimbi said in desperation. ‘But promise me you’ll take me as your wife.’

Suddenly the space echoed with a raucous sound. Hidimba stood behind his sister, shaking with laughter. The next moment, he thundered, ‘So this is how you take care of your brother? Let me first make a pulp of this fool who thinks he is more than a match for me, and then I’ll take care of you.’

‘Please don’t shout,’ Bheema warned Hidimba politely. ‘My mother and brothers are sleeping after a long, tiring journey. They badly need this rest.’ He began to tie his long hair into a knot. Glancing at Hidimbi, he smiled and said, ‘As regards yo

ur sister, you shouldn’t be too harsh with her. She is in love, and a woman in love, you must understand, forgets even her parents, let alone a flesh-eating brother like you.’

‘A woman in love, did you say?’ Hidimba glared at his sister.

‘Brother,’ Hidimbi pleaded, ‘don’t work yourself into a blind rage. Be a good brother and let me marry this handsome man. He is called Bheema. Don’t you think he’ll make a perfect husband for me?’

Hidimba hit her with the back of his hand so hard that she fell backwards.

‘Now this is really too much,’ Bheema growled in rage. ‘I think it’s time I broke that arm of yours.’ And he sprang to his feet like an enraged leopard.

Hidimba let out a piercing cry and rushed at Bheema with outstretched arms. Bheema ducked and gave a hard blow on the rakshasa’s belly. But the giant turned back quickly and charged at Bheema again. They fought like two great tuskers. Hidimbi watched in astonishment as Bheema lifted the giant over and over again and hurled him to the ground. The terrible tumult roused the princes and their mother.

Arjuna cried out, ‘Brother, this is not right. You should have woken me up to tackle this monster. You haven’t slept properly for three nights and you have carried us for several yojanas. You must be tired. Come and rest, and let me finish what you have started.’

Bheema laughed. ‘You know that I don’t like to leave anything half done. Don’t worry. It’s almost over.’ The expert wrestler that he was, he caught the rakshasa by his neck in a powerful grip and twisted it. The giant let out a terrible cry of pain and then the voice went dead, the body limp. Still in a demonic rage, Bheema pummelled the inert body savagely, broke the limbs and flung them out of sight. It took some time for his fury to subside.

Yudhishthira embraced him and exclaimed, ‘With a brother like you, we don’t have to fear any power in the world.’ The others smiled in appreciation, and Kunti’s eyes grew moist with tears of relief and joy. But strangely, Bheema looked rather distressed, as if he regretted killing the brute. He looked around for Hidimbi, wondering where she had disappeared. After a few minutes, Hidimbi came out of the shadows, like a reluctant moon.

‘I’m sorry I had to kill your brother,’ said Bheema, studying her face, which indeed looked sad at the horrible death of her brother. He was a man-eating monster, but hadn’t she grown up with him and lived with him all these years? It was all over now, but could she really forget the past and start a new life?

Hidimbi tried to smile, but tears gushed out of her eyes. ‘My lord,’ she said, checking her tears, ‘don’t regret what you were compelled to do. It was inevitable. Drunk with power, my brother grew too arrogant and cruel and invited his own downfall. Forget it, I love you for what you are; now take me as your wife.’

The others were stunned. This sudden shift from a brutal fight to love was unbelievable. Bheema avoided looking at his family.

‘What’s all this, Bheema? And who is this girl?’ Kunti asked. It was Hidimbi who answered. She told Kunti the whole story and then pleaded, ‘As a woman, you must well know that once a woman gives her heart away to a man, she cannot live without him. You must give your consent, otherwise your son will not marry me.’

Kunti was touched by her sincerity. Despite her magnificent body, Hidimbi looked so tender and vulnerable. A sister of a rakshasa in love with her son! Kunti, the woman, knew love, knew only too well what it meant to be desperately in love. But Kunti, the mother, did not know her son. This was a new Bheema; a Bheema she never realized existed till now. She looked at her eldest son and asked, ‘What do you say, Yudhishthira? Your brother has just won a great fight but has lost his heart.’

‘So,’ asked Yudhishthira, smiling at his brother, ‘what do you say?’

‘I really don’t know…’ Bheema began, but before he could complete his sentence, Arjuna interjected. ‘Yes, certain things are very difficult to know. For instance, love. It happens.’ Bheema blushed, and his family was most amused. Usually, whenever Bheema’s face turned red, everyone knew that that was anger boiling in him and that he could explode any moment. It was a frightening spectacle that put fear in the hearts of people. But now, the brothers laughed watching Bheema’s shy embarrassment. It was a miracle and Hidimbi was the cause.

‘I understand. Go ahead and marry her,’ said Yudhishthira, smiling.

‘But, brother, how can I?’

Affectionately, Yudhishthira touched Bheema’s arm. ‘I know it’s against the convention for a younger brother to take a wife before the elder brother does, but don’t bother too much about it. Rules are there only to be broken. Especially when it comes to love, and when it could make someone happy.’ Bheema could not believe his ears. Was this really the upright Yudhishthira speaking? He saw his mother smile approvingly.

That’s how, in trembling joy, Bheema took Hidimbi as his wife. Kunti blessed them, but with a strict injunction: They could live as man and woman for a year or until a child was born to them, and then Hidimbi had to let Bheema go so he could proceed to Ekachakra with his brothers and mother.

Hidimbi accepted this condition without reservation. She couldn’t have asked for more. She could only hope to be a small chapter in the epic that the Pandavas were. She would learn to be patient and to accept things as they came. Hadn’t she begun an utterly new life, a life she had hitherto seen only in her dreams?

She took the Pandavas to Salivahana and, near a beautiful lake there, built a bamboo cottage for them. She looked to their needs with meticulous care. She brought them luscious fruits from the four corners of the forest. From Kunti, she learnt to cook meat according to their taste. She saw to their comforts constantly, always smiling and cheerful. Only after completing her tasks, when the sun grew soft and endearing, and when Salivahana murmured in the breeze, would she lead Bheema away from the cottage. They would wander about among the trees, swim and play in the lakes and climb the mountains; and when they felt hungry for each other, they would make love fiercely.

Some days, taking pity on her, Kunti would relieve her of the morning duties and ask her to take Bheema and go away. Hidimbi could spend time with Bheema only during the day, for the arrangement was that he would return to the cottage in the evening. Kunti believed that the people of the forest came upon magical powers and communicated with the dark forces of nature during the night. Hidimbi loved Bheema, but Kunti would not trust Hidimbi too much. After all, she was a tribal woman with the traits of the rakshasas in her blood. This was an ancient perception. The forest tribes were seen as descendants of demons who had fought against the gods at the beginning of creation, and therefore, were never to be trusted.

However, Kunti’s strange injunction did not deter the young couple from enjoying life to the hilt. Like children with stars in their eyes, like animals in heat, like gods without the fear of death, they circled the forest hand in hand. They made love by the lake where animals came to drink, by smiling flowers each one as big as a woman’s head. They made love under deep waters and on top of trees. Hidimbi taught her husband the forty-eight ways of tribal love. The art of sucking a mango, the milk-and-water embrace, the throbbing kisses, the blow of a boar, the sporting of sparrow.

Sitting by a lake, all of a sudden she would command, ‘Bite the coral and the jewel.’ And Bheema would go wild with desire. If she became a deer, he became a deer; if she turned into a mare, he turned into a bull. It was the horse and elephant composition he enjoyed most. They made love in Tantric stillness (an art she had picked from the Yamas), suffused with the enchanting, whispering silence of the forest, and then they yielded to wild cries of tearing pain and irrepressible ecstasy, so that the earth itself shuddered with fecund joy. One evening, just after making love by a lake with wondrous lotuses swaying gently in it, surrounded by vibrant flowering bushes and magnificent peepal trees, the sun having painted the horizon with a golden hue, Bheema shouted in joy, ‘I’m blessed. I have no fear of custom and duty, no fear of death. I have touched the source of eternal joy.’<

br />

In this way, as the days passed, even Bheema’s brothers and mother began to live a life of careless joy. It was as if they had been transported back to their idyllic days at Satashringa valley. Kunti forgot her sorrows; Yudhishthira, his conflicts; Arjuna, his ambition; and Nakula and Sahadeva, their eternal sense of inadequacy.

And seven months passed like seven days. Then, one day, their grandfather Vyasa came to see them. He was thin and tall, with a serene face framed by a great silver beard, and looked as wizened as a forest tree. He congratulated Kunti. ‘You took the right decision,’ he said. ‘Hidimbi will bear a brave son to Bheema, and he will be known for his strength and fearlessness. But when he is born, you must leave this place and go to Ekachakra. Worry not too much of your troubles, they are but passing clouds.’

‘But, sir,’ Kunti said, ‘there is no trouble here. We are quite happy, so happy and comfortable that, sometimes, I wonder if we should go to Ekachakra at all.’

Vyasa raised his thinning eyebrows, and then laughed. ‘Kunti,’ he gently rebuked her, ‘forget not yourself. This is but a brief moment in your life. Remember, your sons are born to rule the world.’

Unable to contain himself any longer, Yudhishthira asked, ‘Sir, you are the wise one; please tell me what is more important: to rule the world, or to live without conflict and sorrow?’

‘My dear Yudhishthira, what has happened to you? How can you forget your dharma, your Kshatriya dharma?’

Kshatriya dharma? It sounded like a curse they had been born with, a curse that had uprooted them from the tranquillity of Satashringa and flung them into the chaos of Hastinapura. ‘Why, Grandfather?’ Arjuna asked Vyasa. ‘I don’t understand why I’m bound to lead a Kshatriya life. If I want to, can’t I choose to do something different?’

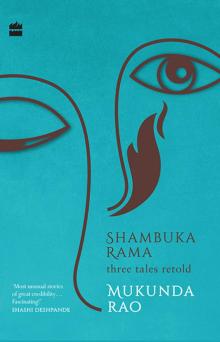

Shambuka Rama

Shambuka Rama